In 2001, Google realized its combined server RAM could hold a full copy of its web index. Moving from disk-based to in-memory systems eliminated slow disk seeks, enabling complex queries with synonyms and semantic expansion. This fundamentally improved search quality long before LLMs became mainstream.

Related Insights

LLMs frequently cite sources that rank poorly on traditional search engines (page 3 and beyond). They are better at identifying canonically correct and authoritative information, regardless of backlinks or domain authority. This gives high-quality, niche content a better chance to be surfaced than ever before.

Managed vector databases are convenient, but building a search engine from scratch using a library like FAISS provides a deeper understanding of index types, latency tuning, and memory trade-offs, which is crucial for optimizing AI systems.

The sudden arrival of powerful AI like GPT-3 was a non-repeatable event: training on the entire internet and all existing books. With this data now fully "eaten," future advancements will feel more incremental, relying on the slower process of generating new, high-quality expert data.

The future of search is not linking to human-made webpages, but AI dynamically creating them. As quality content becomes an abundant commodity, search engines will compress all information into a knowledge graph. They will then construct synthetic, personalized webpage experiences to deliver the exact answer a user needs, making traditional pages redundant.

It's crucial to balance the hype around LLMs with data. While their usage is growing at an explosive 100% year-over-year rate, the total volume of LLM queries is still only about 1/15th the size of traditional Google Search. This highlights it as a rapidly emerging channel, but not yet a replacement for search.

According to Cloudflare's network data, Google's enduring AI advantage comes from its data moat. Its web crawlers access 3.2 times more web pages than OpenAI's, providing a vastly larger training dataset that competitors struggle to match, potentially securing Google's long-term lead.

Google's Titans architecture for LLMs mimics human memory by applying Claude Shannon's information theory. It scans vast data streams and identifies "surprise"—statistically unexpected or rare information relative to its training data. This novel data is then prioritized for long-term memory, preventing clutter from irrelevant information.

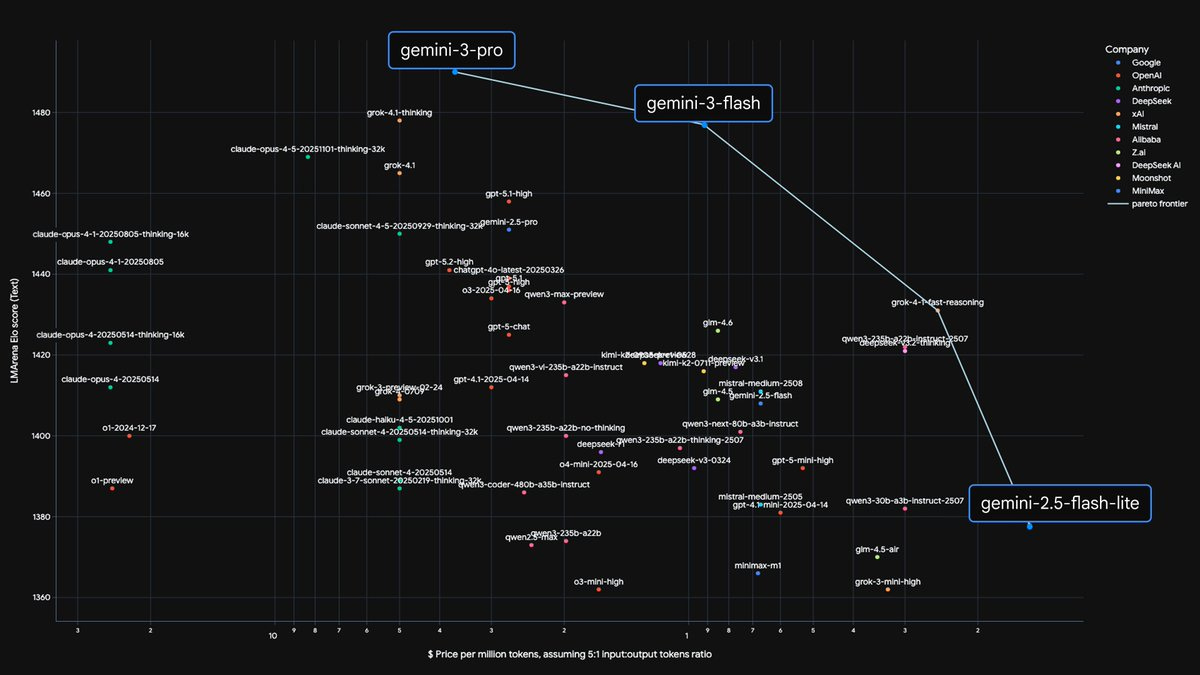

Google's strategy involves creating both cutting-edge models (Pro/Ultra) and efficient ones (Flash). The key is using distillation to transfer capabilities from large models to smaller, faster versions, allowing them to serve a wide range of use cases from complex reasoning to everyday applications.

Vector search excels at semantic meaning but fails on precise keywords like product SKUs. Effective enterprise search requires a hybrid system combining the strengths of lexical search (e.g., BM25) for keywords and vector search for concepts to serve all user needs accurately.

Unlike chatbots that rely solely on their training data, Google's AI acts as a live researcher. For a single user query, the model executes a 'query fanout'—running multiple, targeted background searches to gather, synthesize, and cite fresh information from across the web in real-time.