Doctors are often trained to interpret symptoms arising after stopping psychiatric medication as a relapse of the original condition. However, these are frequently withdrawal symptoms. This common misdiagnosis leads to a cycle of re-prescription and prevents proper discontinuation support.

Related Insights

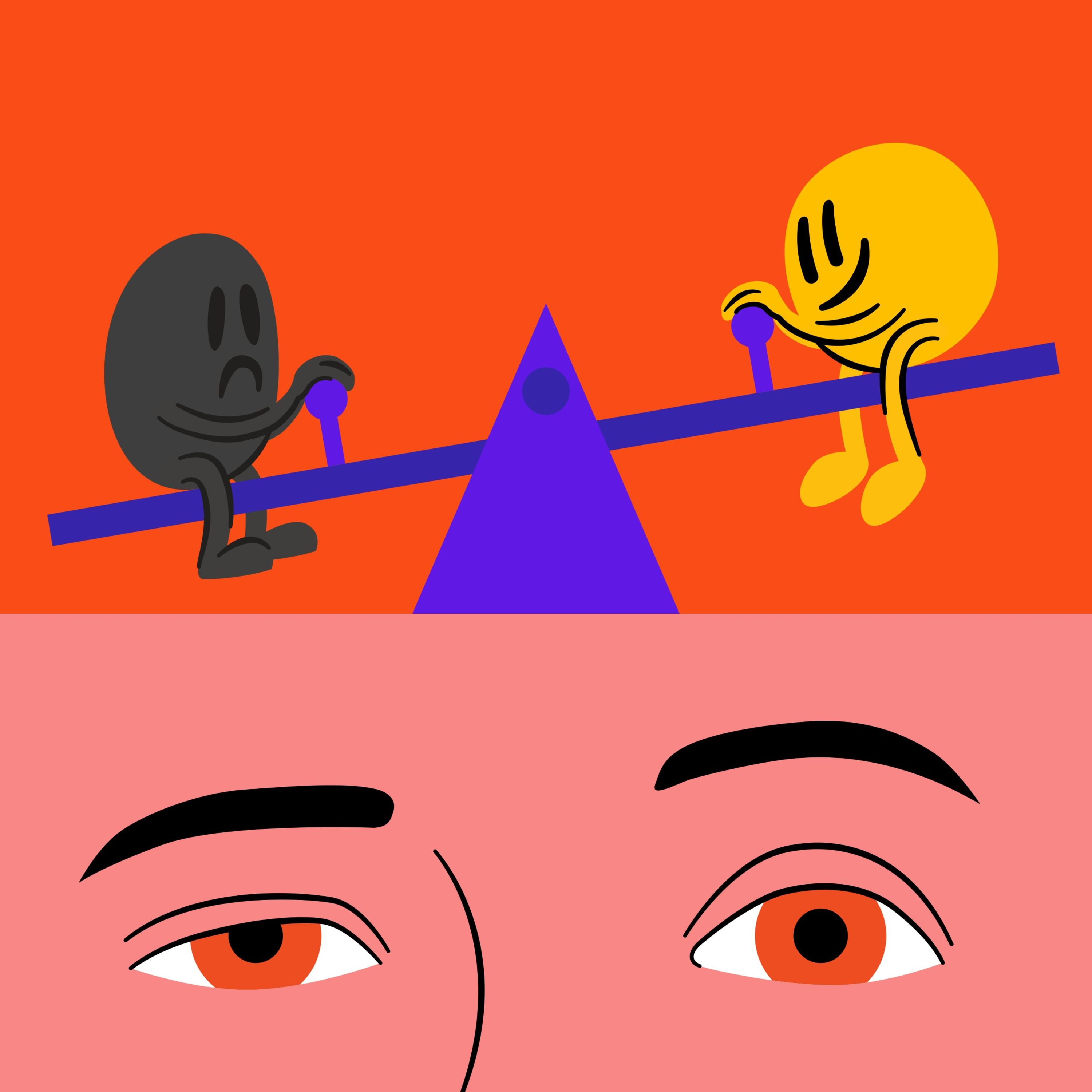

Anxiety often isn't a brain chemistry issue but a physical stress response. A blood sugar crash or caffeine can trigger a physiological state of emergency, and the mind then invents a psychological narrative (like work stress) to explain the physical sensation.

In its rush for the next breakthrough, the field of psychiatry often discards older, effective treatments due to historical stigma. For instance, MAO inhibitors and modern, safer Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) are highly effective for specific depression types but are underutilized because of past negative associations, a phenomenon driven more by politics than science.

For individuals whose symptoms have been repeatedly dismissed, a serious diagnosis can feel like a relief. It provides validation that their suffering is real and offers a concrete problem to address, overriding the initial terror of the illness itself.

Instead of medicating or ignoring symptoms like fatigue or mood swings, view them as your body's way of signaling an underlying issue. By treating symptoms as messages, you can focus on the root cause (like glucose spikes), which makes the 'messages' disappear.

The history of depression treatment shows a recurring pattern: a new therapy (from psychoanalysis to Prozac) is overhyped as a cure-all, only for disappointment to set in as its limitations and side effects become clear. This cycle of idealization then devaluation prevents a realistic assessment of a treatment's specific uses and downsides.

David Baszucki highlights that the most valuable asset in his son's recovery from a manic episode was a small inkling that "things are not quite right." This moment of "insight" is a prerequisite for successful therapy, as without it, patients often resist treatment and flee.

Addiction isn't defined by the pursuit of pleasure. It's the point at which a behavior, which may have started for rational reasons, hijacks the brain’s reward pathway and becomes compulsive. The defining characteristic is the inability to stop even when the behavior no longer provides pleasure and begins causing negative consequences.

Early ADHD research focused on hyperactive boys, ignoring how symptoms present in girls (withdrawal, self-criticism, anxiety). This resulted in a 'lost generation' of women who were treated for anxiety for decades when the underlying issue was actually a neurodivergent condition like ADHD.

The common narrative that recovery ends with a cure is a myth. For many survivors of major illness, the aftermath is the true beginning of the struggle. It involves grappling with post-traumatic stress, a lost sense of identity, and the challenge of reintegrating into a world that now feels foreign.

The term "depression" is a misleading catch-all. Two people diagnosed with it can have completely opposite symptoms, such as oversleeping versus insomnia or overeating versus appetite loss. These are not points on a spectrum but discrete experiences, and lumping them together hinders effective, personalized treatment.