Unlike COVID's growth, which had a hard population limit, AI's potential is tied to energy and computation, which have vast room to expand. However, its real-world application will manifest as a series of S-curves, as different technologies and industries hit temporary plateaus before the next breakthrough occurs.

Related Insights

A 10x increase in compute may only yield a one-tier improvement in model performance. This appears inefficient but can be the difference between a useless "6-year-old" intelligence and a highly valuable "16-year-old" intelligence, unlocking entirely new economic applications.

While Sam Altman's projection for OpenAI to use 250 gigawatts of compute by 2033 seems extreme, it actually charts a slower growth trajectory than the continuous exponential forecasts from analysts like Leopold Aschenbrenner.

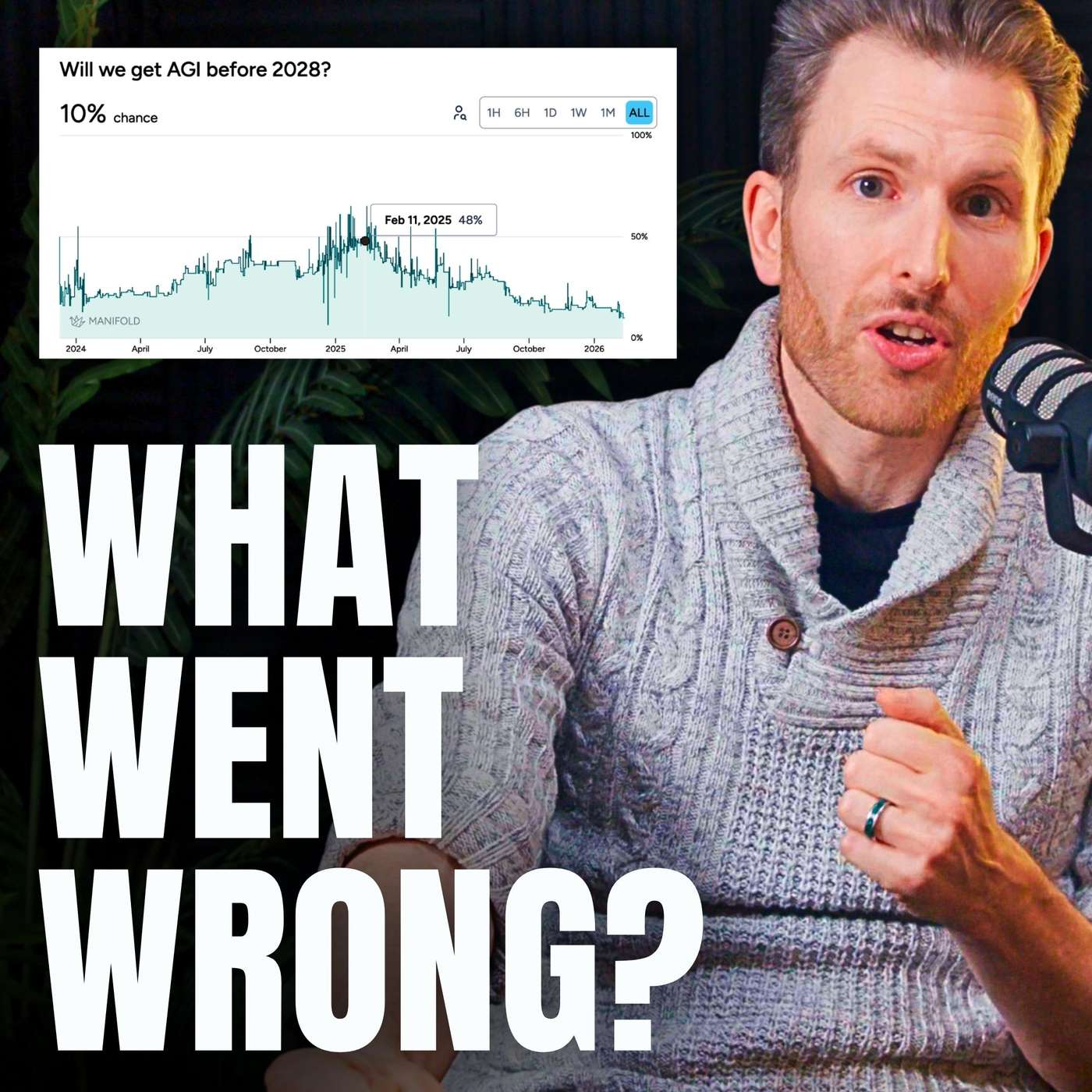

While discourse often focuses on exponential growth, the AI Safety Report presents 'progress stalls' as a serious scenario, analogous to passenger aircraft speed, which plateaued after 1960. This highlights that continued rapid advancement is not guaranteed due to potential technical or resource bottlenecks.

The surprisingly smooth, exponential trend in AI capabilities is viewed as more than just a technical machine learning phenomenon. It reflects broader economic dynamics, such as competition between firms, resource allocation, and investment cycles. This economic underpinning suggests the trend may be more robust and systematic than if it were based on isolated technical breakthroughs alone.

The focus in AI has evolved from rapid software capability gains to the physical constraints of its adoption. The demand for compute power is expected to significantly outstrip supply, making infrastructure—not algorithms—the defining bottleneck for future growth.

Karpathy pushes back against the idea of an AI-driven economic singularity. He argues that transformative technologies like computers and the internet were absorbed into the existing GDP exponential curve without creating a visible discontinuity. AI will act similarly, fueling the existing trend of recursive self-improvement rather than breaking it.

While the long-term trend for AI capability shows a seven-month doubling time, data since 2024 suggests an acceleration to a four-month doubling time. This faster pace has been a much better predictor of recent model performance, indicating a potential shift to a super-exponential trajectory.

The AI industry's exponential growth in consuming compute, electricity, and talent is unsustainable. By 2032, it will have absorbed most available slack from other industries. Further progress will require potentially un-fundable trillion-dollar training runs, creating a critical period for AGI development.

The history of nuclear power, where regulation transformed an exponential growth curve into a flat S-curve, serves as a powerful warning for AI. This suggests that AI's biggest long-term hurdle may not be technical limits but regulatory intervention that stifles its potential for a "fast takeoff," effectively regulating it out of rapid adoption.

Both COVID's spread and technological progress, like AI, appear exponential but are constrained by real-world limits, turning them into logistic or S-curves. Pandemics cap out at population size, while tech hits bottlenecks before the next innovation creates a new growth curve.

![Dylan Patel - Inside the Trillion-Dollar AI Buildout - [Invest Like the Best, EP.442] thumbnail](https://megaphone.imgix.net/podcasts/799253cc-9de9-11f0-8661-ab7b8e3cb4c1/image/d41d3a6f422989dc957ef10da7ad4551.jpg?ixlib=rails-4.3.1&max-w=3000&max-h=3000&fit=crop&auto=format,compress)