The "epsilon-grounded" simulation approach has a hidden cost: its runtime is inversely proportional to epsilon. To be very certain that simulations will terminate (a small epsilon), agents must accept potentially very long computation times, creating a direct trade-off between speed and reliability.

Related Insights

In multi-agent simulations, if agents use a shared source of randomness, they can achieve stable equilibria. If they use private randomness, coordinating punishment becomes nearly impossible because one agent cannot verify if another's defection was malicious or a justified response to a third party's actions.

Simulating strategies with memory (like "grim trigger") or with multiple players causes an exponential explosion of simulation branches. This can be solved by having all simulated agents draw from the same shared sequence of random numbers, which forces all simulation branches to halt at the same conceptual "time step."

Contrary to the expectation that more agents increase productivity, a Stanford study found that two AI agents collaborating on a coding task performed 50% worse than a single agent. This "curse of coordination" intensified as more agents were added, highlighting the significant overhead in multi-agent systems.

Purely agentic systems can be unpredictable. A hybrid approach, like OpenAI's Deep Research forcing a clarifying question, inserts a deterministic workflow step (a "speed bump") before unleashing the agent. This mitigates risk, reduces errors, and ensures alignment before costly computation.

Despite different mechanisms, advanced cooperative strategies like proof-based (Loebian) and simulation-based (epsilon-grounded) bots can successfully cooperate. This suggests a potential for robust interoperability between independently designed rational agents, a positive sign for AI safety.

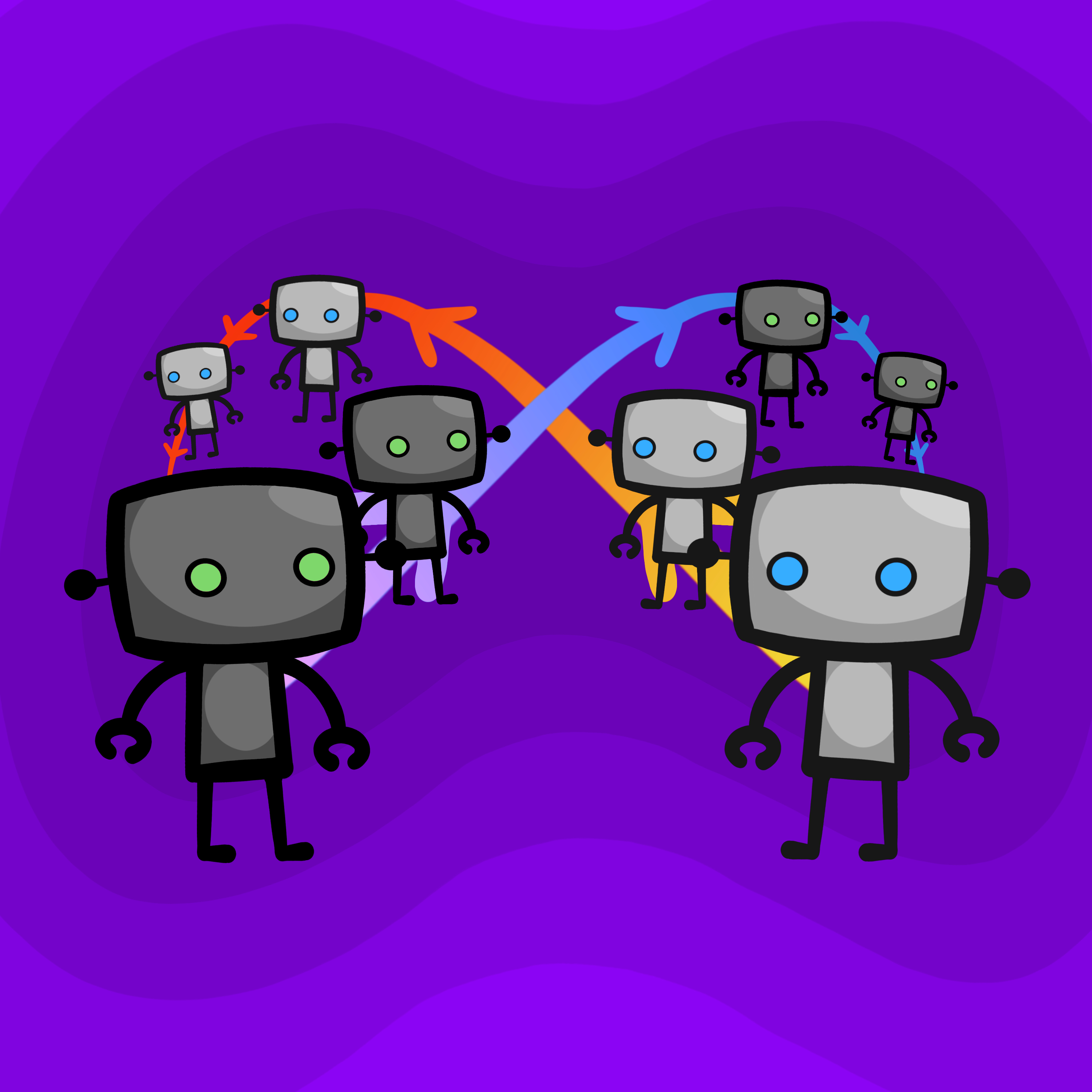

Softmax's technical approach involves training AIs in complex multi-agent simulations to learn cooperation, competition, and theory of mind. The goal is to build a foundational, generalizable model of sociality, which acts as a 'surrogate model for alignment' before fine-tuning for specific tasks.

The performance gap between solo and cooperating AI agents was largest on medium-difficulty tasks. Easy tasks had slack for coordination overhead, while hard tasks failed regardless of collaboration. This suggests mid-level work, requiring a balance of technical execution and cooperation, is most vulnerable to coordination tax.

Creating realistic training environments isn't blocked by technical complexity—you can simulate anything a computer can run. The real bottleneck is the financial and computational cost of the simulator. The key skill is strategically mocking parts of the system to make training economically viable.

A key finding is that almost any outcome better than mutual punishment can be a stable equilibrium (a "folk theorem"). While this enables cooperation, it creates a massive coordination problem: with so many possible "good" outcomes, agents may fail to converge on the same one, leading to suboptimal results.

A simple way for AIs to cooperate is to simulate each other and copy the action. However, this creates an infinite loop if both do it. The fix is to introduce a small probability (epsilon) of cooperating unconditionally, which guarantees the simulation chain eventually terminates.