There is a temptation to create a flurry of AI-specific laws, but most harms from AI (like deepfakes or voice clones) already fall under existing legal categories. Torts like defamation and crimes like fraud provide strong existing remedies.

Related Insights

Instead of trying to anticipate every potential harm, AI regulation should mandate open, internationally consistent audit trails, similar to financial transaction logs. This shifts the focus from pre-approval to post-hoc accountability, allowing regulators and the public to address harms as they emerge.

Universal safety filters for "bad content" are insufficient. True AI safety requires defining permissible and non-permissible behaviors specific to the application's unique context, such as a banking use case versus a customer service setting. This moves beyond generic harm categories to business-specific rules.

India is taking a measured, "no rush" approach to AI governance. The strategy is to first leverage and adapt existing legal frameworks—like the IT Act for deepfakes and data protection laws for privacy—rather than creating new, potentially innovation-stifling AI-specific legislation.

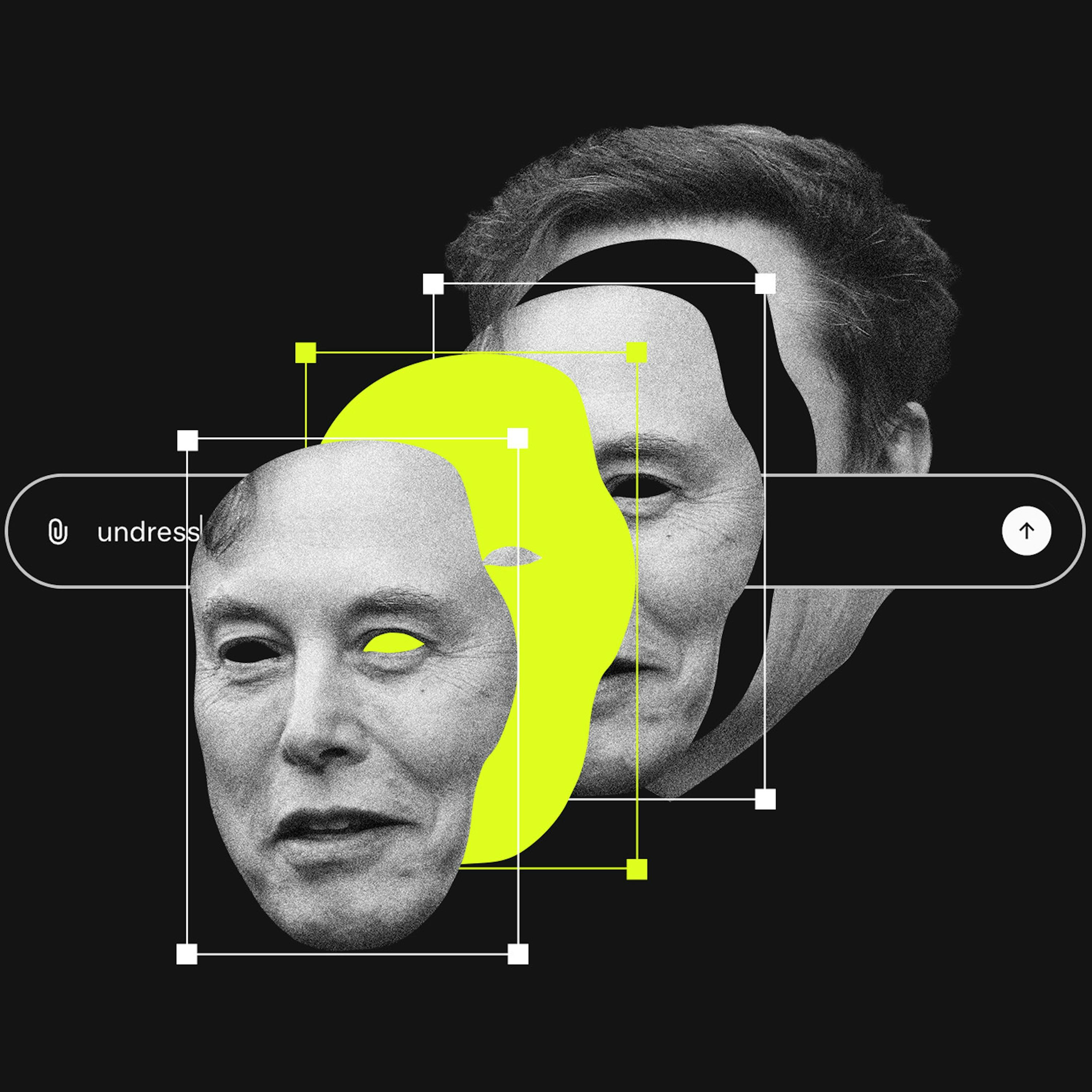

The Grok controversy is reigniting the debate over moderating legal but harmful content, a central conflict in the UK's Online Safety Act. AI's ability to mass-produce harassing images that fall short of illegality pushes this unresolved regulatory question to the forefront.

The rush to label Grok's output as illegal CSAM misses a more pervasive issue: using AI to generate demeaning, but not necessarily illegal, images as a tool for harassment. This dynamic of "lawful but awful" content weaponized at scale currently lacks a clear legal framework.

Instead of trying to legally define and ban 'superintelligence,' a more practical approach is to prohibit specific, catastrophic outcomes like overthrowing the government. This shifts the burden of proof to AI developers, forcing them to demonstrate their systems cannot cause these predefined harms, sidestepping definitional debates.

The UK's strategy of criminalizing specific harmful AI outcomes, like non-consensual deepfakes, is more effective than the EU AI Act's approach of regulating model size and development processes. Focusing on harmful outcomes is a more direct way to mitigate societal damage.

Section 230 protects platforms from liability for third-party user content. Since generative AI tools create the content themselves, platforms like X could be held directly responsible. This is a critical, unsettled legal question that could dismantle a key legal shield for AI companies.

Insurers like AIG are seeking to exclude liabilities from AI use, such as deepfake scams or chatbot errors, from standard corporate policies. This forces businesses to either purchase expensive, capped add-ons or assume a significant new category of uninsurable risk.

AI companies argue their models' outputs are original creations to defend against copyright claims. This stance becomes a liability when the AI generates harmful material, as it positions the platform as a co-creator, undermining the Section 230 "neutral platform" defense used by traditional social media.