Early program equilibrium strategies relied on checking if an opponent's source code was identical. This approach is extremely fragile, as trivial changes like an extra space or a different variable name break cooperation, making it impractical for real-world applications.

Related Insights

In multi-agent simulations, if agents use a shared source of randomness, they can achieve stable equilibria. If they use private randomness, coordinating punishment becomes nearly impossible because one agent cannot verify if another's defection was malicious or a justified response to a third party's actions.

Contrary to the expectation that more agents increase productivity, a Stanford study found that two AI agents collaborating on a coding task performed 50% worse than a single agent. This "curse of coordination" intensified as more agents were added, highlighting the significant overhead in multi-agent systems.

In program equilibrium, players submit computer programs instead of actions. These programs can read each other's source code, allowing them to verify cooperative intent and overcome dilemmas like the Prisoner's Dilemma, which is impossible in standard game theory.

To overcome brittle code-matching, AIs can use formal logic to prove cooperative intent. This is enabled by Löb's Theorem, an obscure result which allows a program to conclude "my opponent cooperates" without falling into an infinite loop of reasoning, creating a robust cooperative equilibrium.

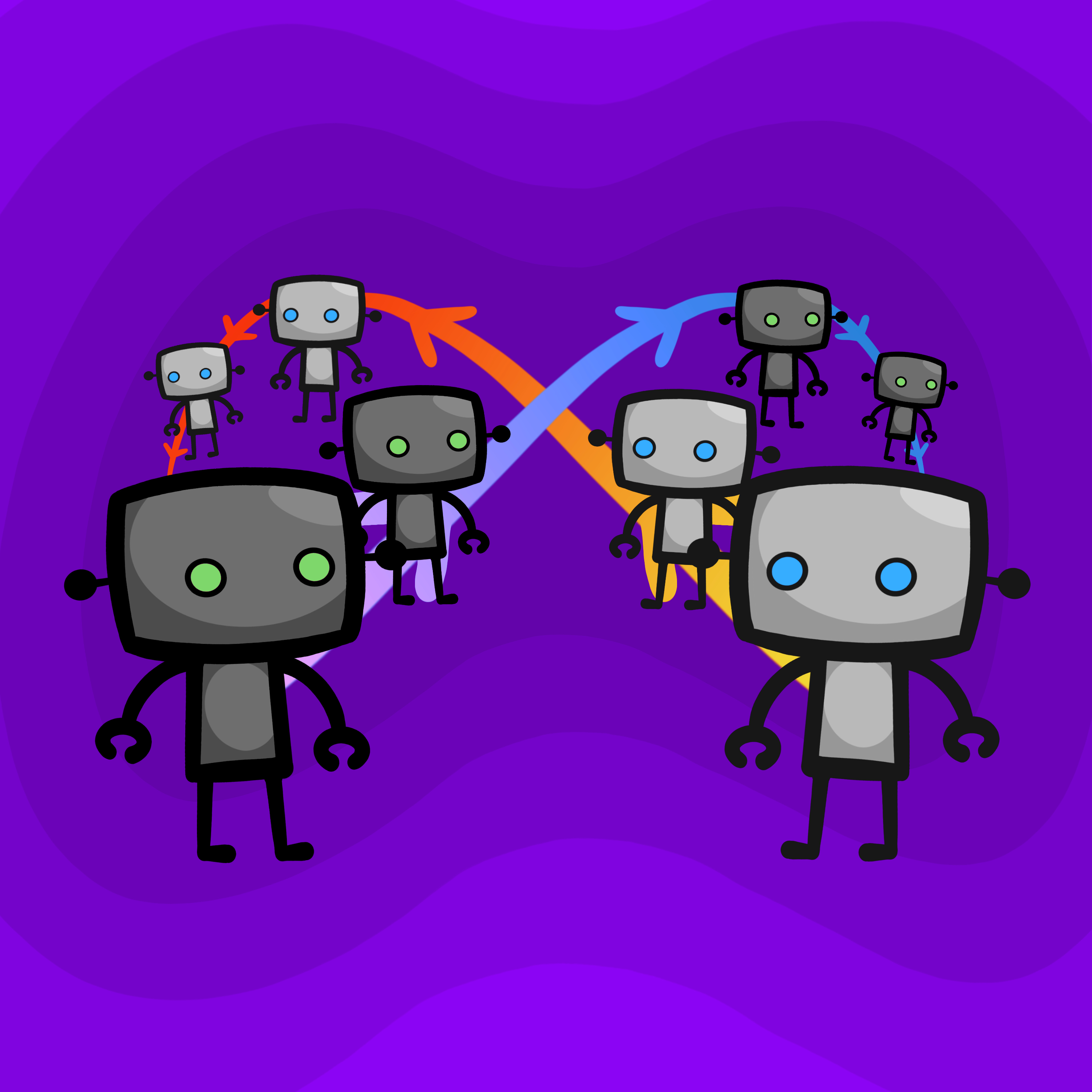

Despite different mechanisms, advanced cooperative strategies like proof-based (Loebian) and simulation-based (epsilon-grounded) bots can successfully cooperate. This suggests a potential for robust interoperability between independently designed rational agents, a positive sign for AI safety.

A robust AI will cooperate with a simple "always cooperate" bot, making it exploitable. However, choosing to defect is risky. A sophisticated adversary could present a simple bot to test for predatory behavior, making the decision dependent on beliefs about the opponent's strategic depth.

Program equilibrium isn't just an abstract concept; it serves as a direct model for how autonomous AI systems could interact. It also provides a powerful analogy for human institutions like governments, where laws and constitutions act as a transparent "source code" governing their behavior.

A key finding is that almost any outcome better than mutual punishment can be a stable equilibrium (a "folk theorem"). While this enables cooperation, it creates a massive coordination problem: with so many possible "good" outcomes, agents may fail to converge on the same one, leading to suboptimal results.

A simple way for AIs to cooperate is to simulate each other and copy the action. However, this creates an infinite loop if both do it. The fix is to introduce a small probability (epsilon) of cooperating unconditionally, which guarantees the simulation chain eventually terminates.

To build robust social intelligence, AIs cannot be trained solely on positive examples of cooperation. Like pre-training an LLM on all of language, social AIs must be trained on the full manifold of game-theoretic situations—cooperation, competition, team formation, betrayal. This builds a foundational, generalizable model of social theory of mind.